Why Honda’s Most Ambitious Engine Had to Fail

Yes, Honda Did It First!

Our recent article about Ferrari’s pill-shaped piston patent had a lot of readers commenting that Honda did it decades ago with their NR engine project. While Honda had their distinct reasons for going this route, and their execution was markedly different from what Ferrari is exploring, it is a fact that the Japanese manufacturer was the first to envision oval pistons and combustion chambers way back in the ‘70s.

Racing Drives Innovation

Innovation in the internal combustion space today usually revolves around creating cleaner, more efficient engines. The focus is on efficiency, emissions, downsizing, electrifying, or uncovering means to hold off obsolescence. In the mid-20th century, though, racing was the driving force behind motorcycle development, and Honda was one of the great innovators.

New Racing

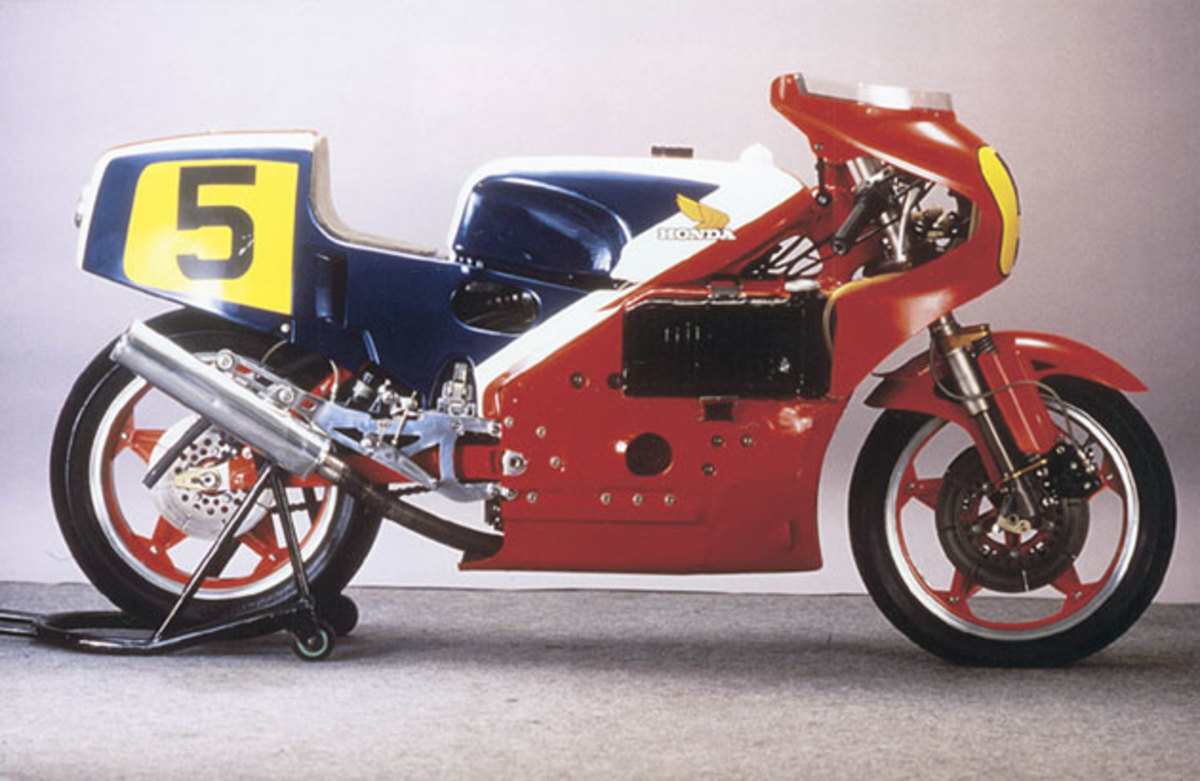

The brand dominated the sport with technologically-advanced, multi-cylinder, four-stroke machinery in the 1960s, eventually stepping away from motorcycle racing in 1968 to focus on developing and building passenger cars. In the late ’70s, after a hiatus of over a decade, founder Soichiro Honda wanted back in and set up the NR or New Racing project with the aim of competing in the Grand Prix Motorcycle World Championship, which is now MotoGP, the premier class of motorcycle racing.

There was one problem: the sport was then dominated by two-stroke machinery. Soichiro Honda strongly disliked two-stroke engines, considering them noisy, inefficient, and unsophisticated, and set about attempting to create a revolutionary four-stroke motor that could outperform two-stroke engines of equal cubic capacity. The oval-piston engine, while legendary, is the result of this ultimately unsuccessful experiment.

Honda

Two-Stroke Supremacy

Pound-for-pound, two strokes can make much more power than four strokes simply because they fire twice as often and complete the entire combustion cycle twice as fast — in one rather than two full crank rotations. To put this into perspective, the last time we saw two- and four-stroke machinery compete in the same class, it was 990cc four strokes and 500cc two strokes sharing the grid in 2002 and ‘03. But four strokes didn’t get these displacement allowances back in the ‘70s and ‘80s.

The rules were simple: no more than four cylinders, no more than 500cc in displacement. And the team of engineers at Honda’s NR project was faced with the problem of how to build a four-stroke motor that could ingest, combust, and expel air (and fuel) twice as fast as previously thought possible.

Valve Area Woes

The answer to Honda’s problem was simple, on paper at least. A two-stroke engine sees twice as many power strokes as a four-stroke engine spinning at the same RPM. So, to match a two-stroke motor’s power output, a four-stroke would have to spin twice as fast. The successful two-stroke race machines of the time were spinning up to over 10,000 rpm and creating upwards of 120 hp; Honda set itself a target of 23,000 rpm and 130 hp, and got to work.

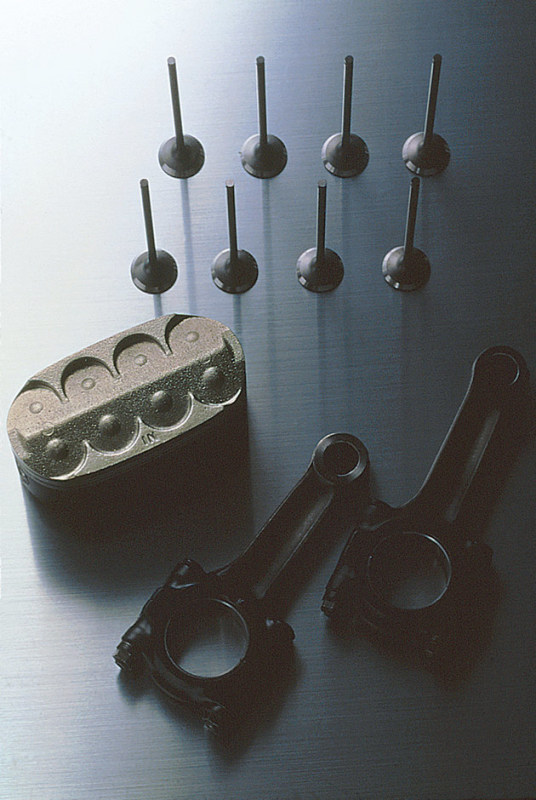

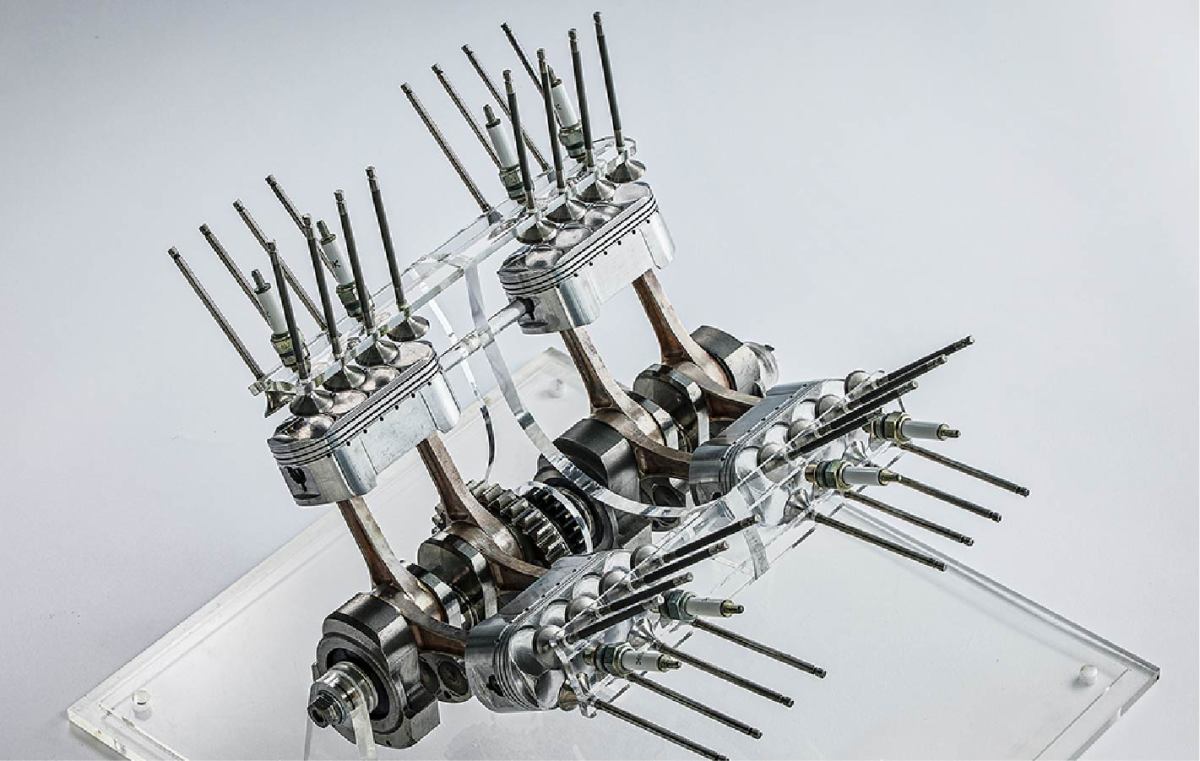

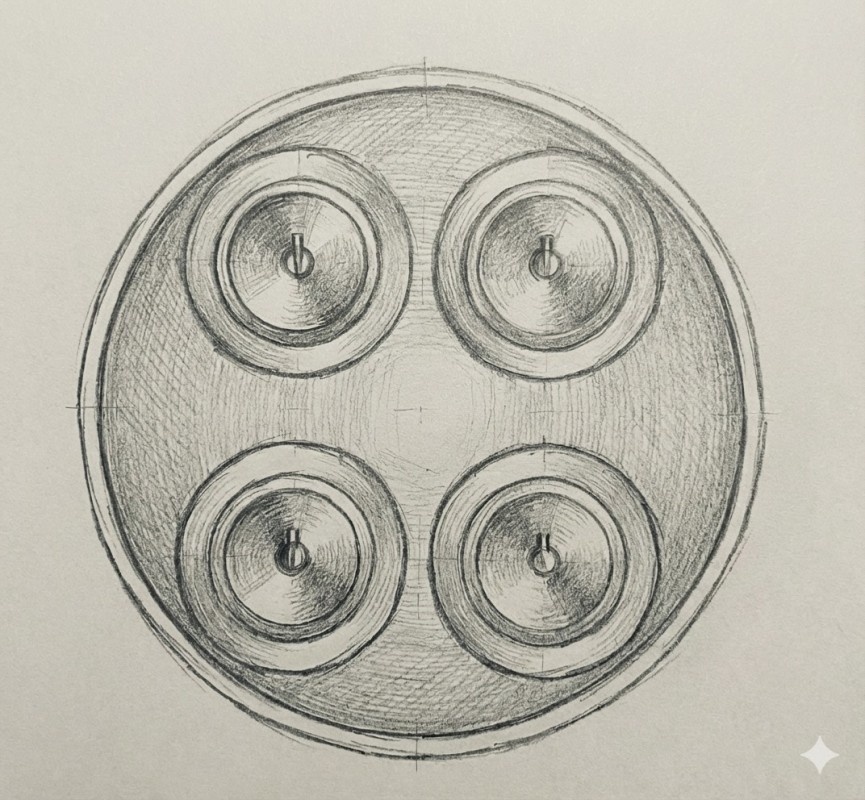

There are many physical limitations standing in the way of how fast an engine can spin, but to even stand a chance, Honda’s engineers had to first come up with a way to pump enough air through a 500-cc four-cylinder motor to sustain itself at stratospheric revs. More valve area was the need of the hour, but space was limited within the confines of a round, capacity-limited cylinder. Honda couldn’t increase the size of the combustion chamber to accommodate more valves, but the rules didn’t say anything about its shape. And so the oval combustion chamber was born, crafted to accommodate eight lightweight valves per cylinder for a total of 32 valves for this unique V4 motor with the breathing capacity of a V8.

Reinventing the Wheel

Piston engine combustion chambers have always been round, simply because this smooth, uniform shape offers the best seal. Trying to change this tried and tested design to accommodate more valves was akin to reinventing the wheel, and threw up a whole lot of issues during development. One was maintaining a seal within the cylinder for the duration of a race — oval piston rings had to be developed to tackle this, and their manufacture at the required tolerances pushed the limits of the time’s machining capabilities.

Another issue was the excessive rocking of an oblong piston as it changed direction; this was countered by the incorporation of two connecting rods per piston, but an undesirable side effect was more weight and reciprocating mass. Even the piston wrist pins had to be inordinately long to cover the distance between the two connecting rods, and these longer pins could flex under the extreme forces of high-rpm operation.

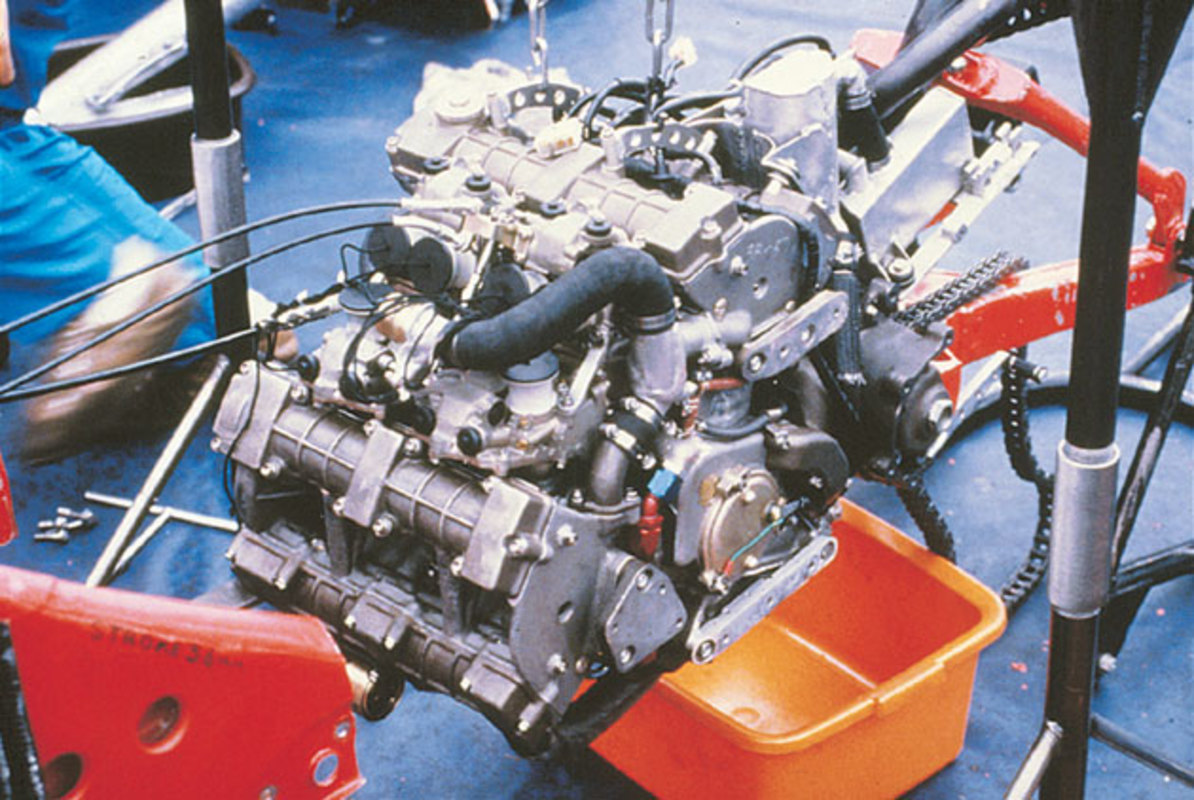

Going Racing

The first time Honda’s NR500 saw the grid was at the 1979 British GP; unfortunately, both bikes entered failed to complete the race, and were utterly outclassed by the two-stroke competition. The bike continued racing for the next two seasons as the engineers attempted to further refine and make it more competitive, ultimately getting the motor to rev up to 19,500 rpm and generate 130 hp. This, however, was not enough to make up for the weight of the complex motor, and the experimental NR500 failed to leave a mark on the championship. Honda finally gave in, retired the oval-piston NR500 in early 1982, and focused on developing the NS500 three-cylinder two-stroke machine that eventually won the 1983 championship.

A Failed Experiment?

Yes, Soichiro Honda failed at proving that a four-stroke motor could compete with two strokes on equal footing, and spent an inordinate amount of time and money in doing so. While the NR project didn’t have the desired impact on racing, it did make massive contributions to motorcycle technology. The need to manufacture small parts to extremely precise tolerances drove the development of better machining technology, while the NR500 also pioneered the use of exotic metals, like magnesium and titanium, to save weight, as well as the use of a slipper clutch — something we see even on beginner bikes today. While the oval-piston NR500 engine wasn’t the racing success it was intended to be, its existence is a showcase of internal combustion innovation at its best.

The Oval Piston Road Bike

Honda may have abandoned their oval-piston race project in the ‘80s, but their engineers had successfully proved that the concept worked. And what better proof of concept than bringing this technology to a road-legal motorcycle. In 1992, Honda launched the NR750 — a limited-run halo product and tribute to the NR500 race project, equipped with the oval piston technology developed at the track over a decade ago.

Only around 300 were built, not for profit but to make a statement. Not as high-strung and hence less fragile than the 500cc race engine, the NR750 revved to 16,000 rpm and made 125 hp. Priced at around $60,000 in 1992 (around $138,000 in today’s money), it was one of the most expensive and exclusive motorcycles of the ‘90s, aimed at collectors who wanted to own a unique piece of engineering excellence. Today, this motorcycle commands almost mythical status and six figures when, and if, one comes up for sale.